Jim Stephenson: Time and Motion

Text by Jim Stephenson

In December 2021, the photographer and filmmaker Jim Stephenson presented a glimpse in to his practice and methodology as part of the Building on the Built talks series. Here we present a short extract from that presentation.

Many of Jim’s films are available to watch online here.

JS For over 100 years cinema has adopted architecture as a storytelling device and even a central character. Always present, always driving others movements and motivations.

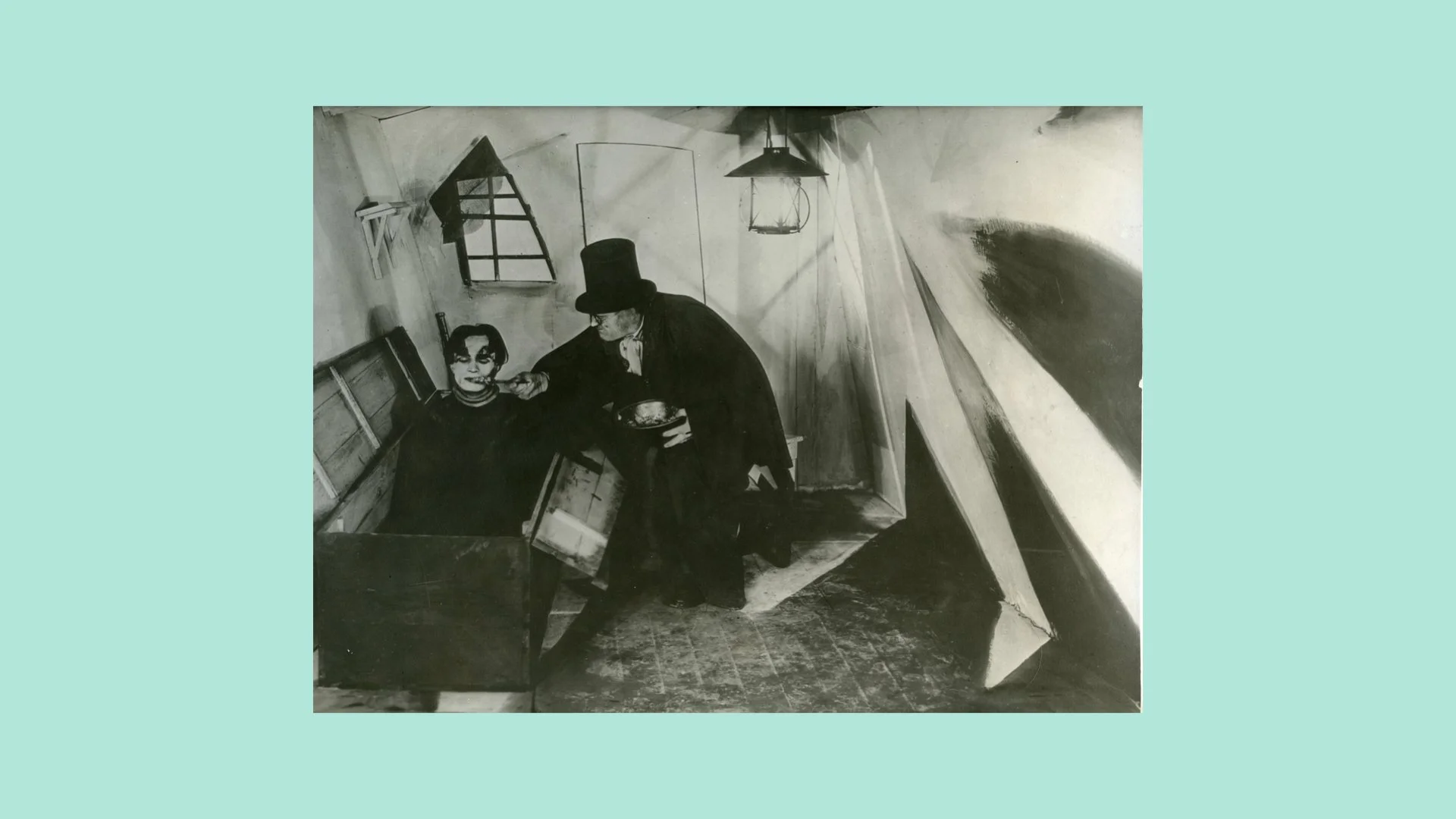

This is a still from The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (Robert Weine, 1920). The sets, with their sloping walls and architectural paradoxes, are a great example of German expressionism and here the architecture of the Dr’s house reflects his state of mind. In this instance the architecture expresses internal paranoia, chaos and confusion.

So how can we use the tools of cinema to tell stories about architecture? There are three principle methods we use.

The first is Mis-en-Scene. Everything in front of the camera and what visual cues and messages they give to the viewer. In our non-fiction films we can’t set dress, but we can use context, composition, lighting, camera proximity, shadow and texture to tell an unspoken story.

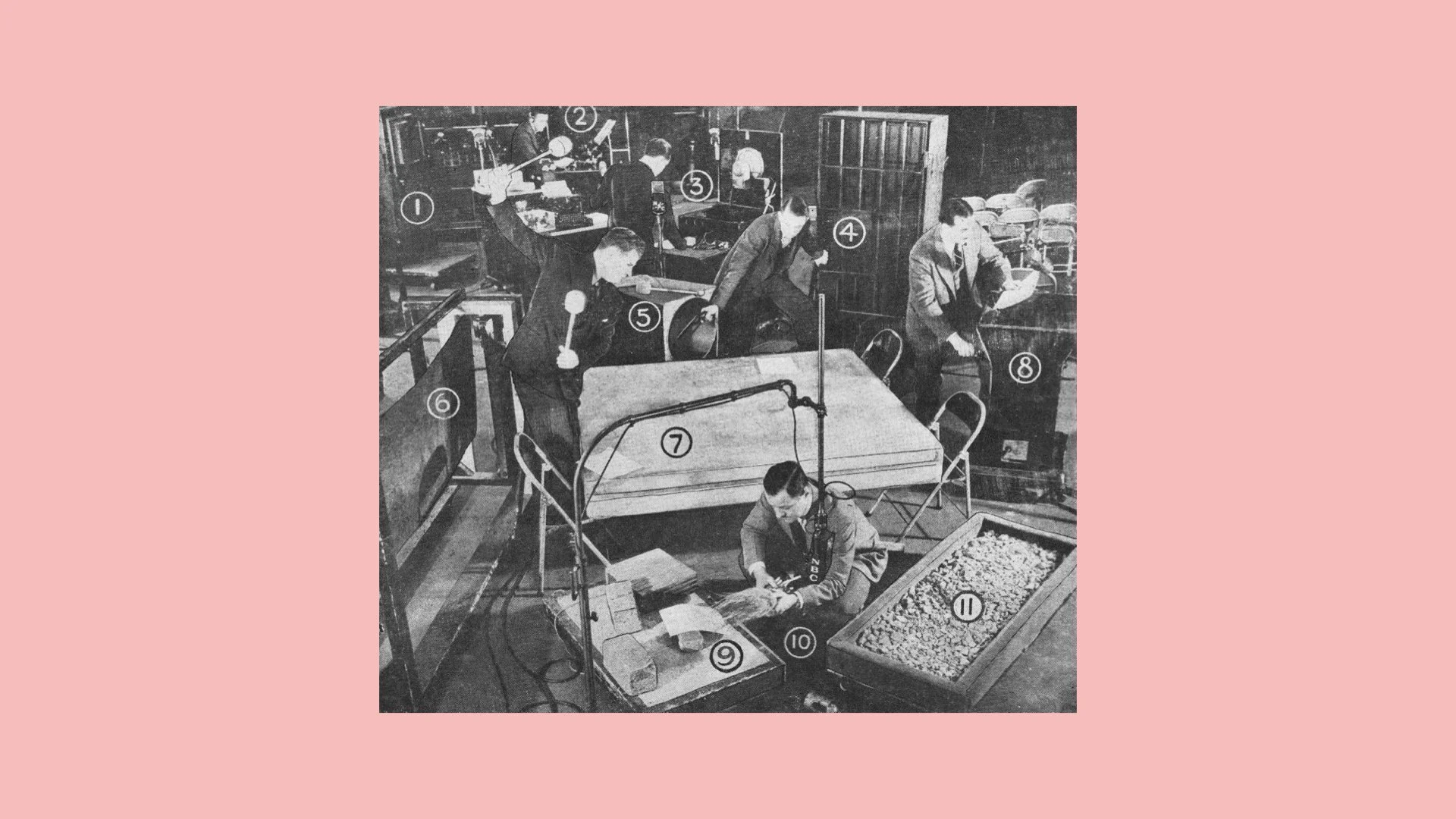

The second tool we adopt is sound. The aural treatment of our films drives at least 50% of the story, if not more.

We layer a mixture of ambient sounds, library sounds, music and dialogue to create a textured soundscape with the intention of placing the audience in the space.

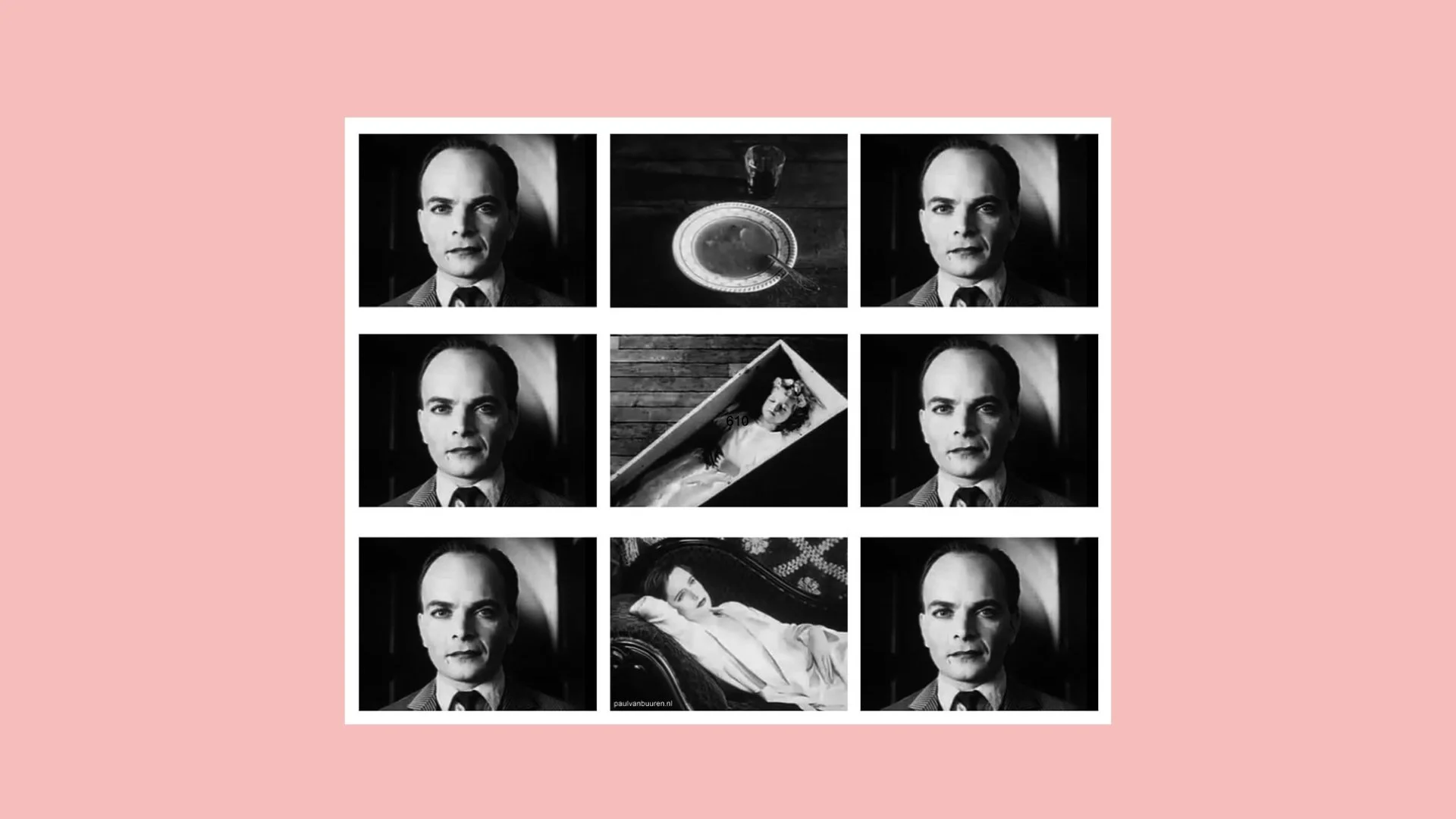

The third of the tools is arrangement - acknowledging how each individual clip has an effect on the ones before and after it.

The image above is an illustration of The Kuleshov Effect. Lev Kuleshov was a Russian film maker in the early 20th century and he pioneered the use of the mental phenomenon by which viewers derive more meaning from the interaction of two sequential shots that from a single shot in isolation. In this instance he filmed movie star Ivan Mosjoukine stare dispassionately at the camera and then made three new versions of the footage by inserting an image of a bowl of soup, a child in a coffin and a women reclining on a couch in the middle. Audiences marvelled at Mosjoukine’s ability to infer hunger, grief and lust through his eyes and face, even though in reality the shots of him never change.

We can use this to great effect in films of architecture.

The buildings we make films about already exist.

Much of our work is about observation. It’s slow and meditative. Watching how people and light interact with the building, it’s spaces and it’s materials.

The aim is to use these observations and these tools taken from cinema to give the viewer the chance to build in their head a Cinematic Space - the idea of what a building not just looks like, but what it feels like as well.

We can’t replicate the experience of being there in person. We’re creating a new, imagined architectural space. Close, but not like the real one and in this way, we’re building on the built.

NOTES

Thanks to Jim Stephenson for his wonderful talk in December 2021 and for sharing this edited version with us.

Posted March 17th 2022