Fred Scott: The Double Ecstasy of Altering Architecture

Review by Peter Youthed

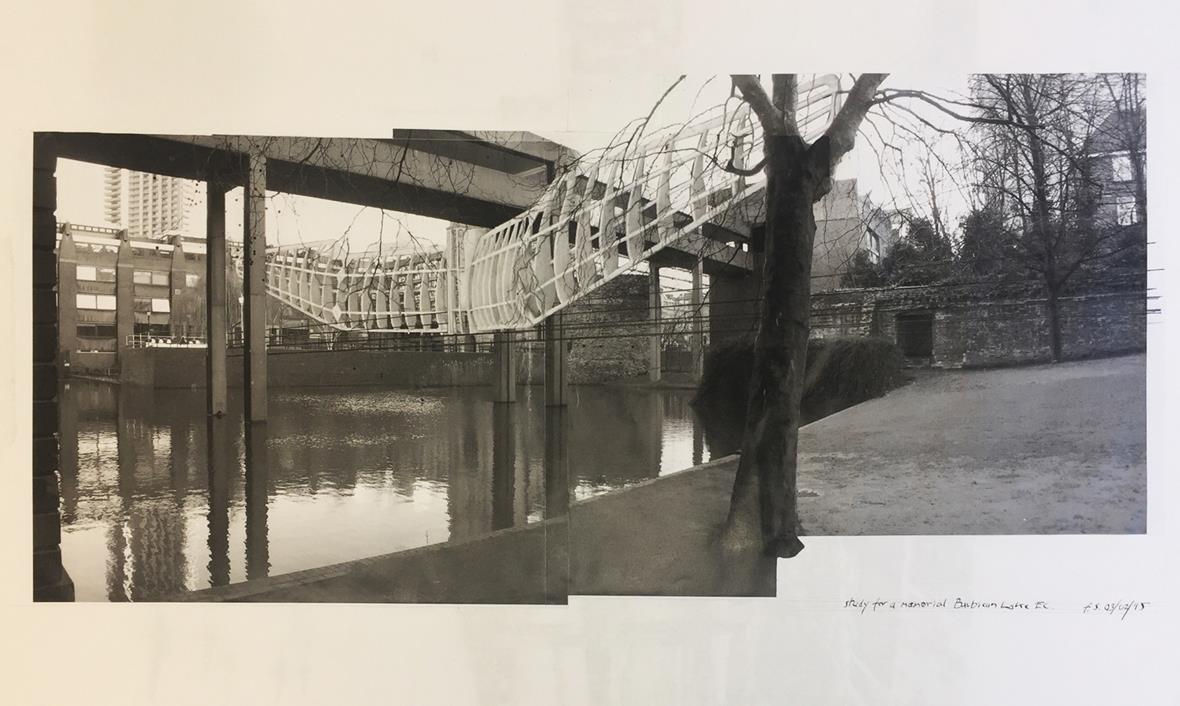

Fred Scott, Study for a Memorial, Barbican Lake EC, 2015

Books focused on interventional work on existing buildings often take one of three approaches: (1) the classification of interventional work by the type of building involved (e.g. barns, castles, warehouses, the terrace house, etc) (2) the technical aspects of the work (i.e. bringing a building’s fabric in line with current regulations or improving its environmental performance) or (3) the strategic approach taken by the designer (e.g. extending a house in the same style, inserting new domestic facilities in to an industrial ‘loft’ or salvaging elements of the built fabric of an old building to create new spaces, etc).

Fred Scott’s approach, captured in his book On Altering Architecture (Routledge, 2008) and shared with generations of students through his teaching, is almost unique in that it takes a more theoretical approach to building in existing fabric and situates interventional work within a wider cultural framework; by drawing comparisons with art conservation, through discussion of the nature of the modernity, ruin, the function of copying and reproduction and exploring the psychological and sociological aspects of transforming existing buildings, Scott’s thinking illuminates relatively unexplored territory. Scott reveals the ‘transgressive’ nature of alteration work that breaks the taboos of restoration and conservation and discloses the presence of the surreal in even the most everyday of architectural transformations.

A key point of departure for Scott’s thought are two contrasting approaches to interventional work, personified by two nineteenth century figures; the writer and patron of the arts John Ruskin, and his contemporary, the French architect Violet-le-Duc. For Ruskin the beauty of great architecture was irrevocably destroyed by restoration but for Violet-le-Duc restoration work could, conversely, enable an existing building to achieve “a perfection that may never have existed at any given time”.

Scott’s sympathies lie with Violet-le-Duc, and his book and lectures cite numerous examples of beautiful, hybrid works of architecture that have lived lives beyond their original use, arguing for an essentially progressive position that looks toward the revitalisation, rather than obsolescence, of works of architecture. A position that, if nothing else, encourages an alternative to the environmentally catastrophic, tabula rasa approach that underpins so much of the construction sector.

Scott’s thinking can be detected in much of the now high-profile interventional work that UK-based practices have undertaken since the publication of his book a decade ago; from the ongoing work on the Neues Museum in Berlin by David Chipperfield, via the Sterling Prize winning Astley Castle by Witherford, Watson Mann and the rich seam of work produced by practices like 6A and Caruso St John, through to the recently completed work at Goldsmiths College by Assemble.

Scott describes interventional work “as being the agent of temporality, of the re-colonisation of the existing, but equally the agent of the abiding”. I would suggest that this description of the Janus-headed nature of interventional architecture also aptly informs the practice of creating ‘new’ architecture. Scott’s championing of the role of collage as a design tool and his recognition of the essentially open-ended or ‘unfinished’ nature of architecture are valuable contributions to contemporary practice.

For Scott, architectural design, at its best, is a kind of ‘Bacchic delirium’ where opposites are reconciled and great architecture navigates a skillful trajectory between the excessive fetishisation of the ‘new’ and the senseless preservation, or reproduction, of historical fabric for it’s own sake.

Notes

A version of this essay originally appeared in the Briefing section of Building Design, 18th October 2018