Site Specific: The Quay

T O B Architect - Ramelton, 2022

Architect Thomas O’Brien is based in Dublin, Ireland and established his practice, T O B Architect, in 2013. He is a Design Fellow at University College Dublin, where he graduated in 2005 and currently teaches in the first and fifth year studios.

A second project by TOB Architect, J&R House, has been added to our Archive here and you can also read an conversation between Tom with Architecture Ireland’s editor Michael K Hayes here.

TOB The word repair comes to the English language through French from Latin; re: back and parer: make ready. A repair, understood this way is not the same as making something ‘as good as new’, it is to make a thing ready again. A significant attribute of a repair is to perpetuate a thing in continued purpose as opposed to conserving it as an artefact. If strict conservation seeks to petrify, a repair could be said to acknowledge the impossibility of such an intention.

The town of Ramelton (Rath Mealtainn) was established between 1609 and 1622 when the lands around it were acquired by an English mercenary: Sir William Stewart during the Ulster Plantation. In the 18th and 19th century, the town prospered as a colonial port with trade extending to Great Britain, North America, Norway and the Caribbean, and the stone warehouses built around 1830 on the River Lennon quays, remain to tell of that contentious history, and perhaps the stone walls out of which these buildings were constructed still hold the history of the rath or fort that once stood at the mouth of The Lennon river as it enters Lough Swilly. The prosperity of this small town waned when the railway came to the nearby town of Letterkenny in the late 19th century and these buildings in the 20th century came to be known as The Bottling Stores in reference to their new function as warehousing for a local lemonade manufacturer.

Long durations of time allow for a vast expanse of forgetting and remembering, and the ‘completed’ building is not really what was gestured at the beginning. I find it easier in retrospect to remember the project as a durational composite (a dream?) of conversations, reactions and judgements. I should expand even this though, to envelope the history and cultural context of the building, and also the future of this building. Maybe all I can say is that there isn’t really a beginning or an end when one works with an existing building.

We can describe the pragmatics of the project:

The client is an interesting positive person, who bought this last warehouse on the quays along with a couple of other buildings during the last recession at low cost. He had experience in construction and a desire to save these buildings from the dereliction and neglect affecting other buildings along the quay.The eventual brief after discussing differing configurations, was to insert two houses into one of these warehouses.

The project was steered by a number of useful constraints:

The quay’s historical and visual status as an iconic piece of town fabric meant that minimum alterations to its external envelope were allowed by the municipality.

The existing floor to ceiling heights were very low at approximately 2 meters

The quays tend to flood on an annual basis when spring tides coincide with heavy rainfall and the increased surge of the river.

The building has no private outdoor space. It overlooks neighbouring properties to the rear and the south elevation, but does enjoy the vibrant public space of the quay on the west and north sides.

Though the existing envelope was not really large enough, the client required two dwelling houses, one for himself and one for his children

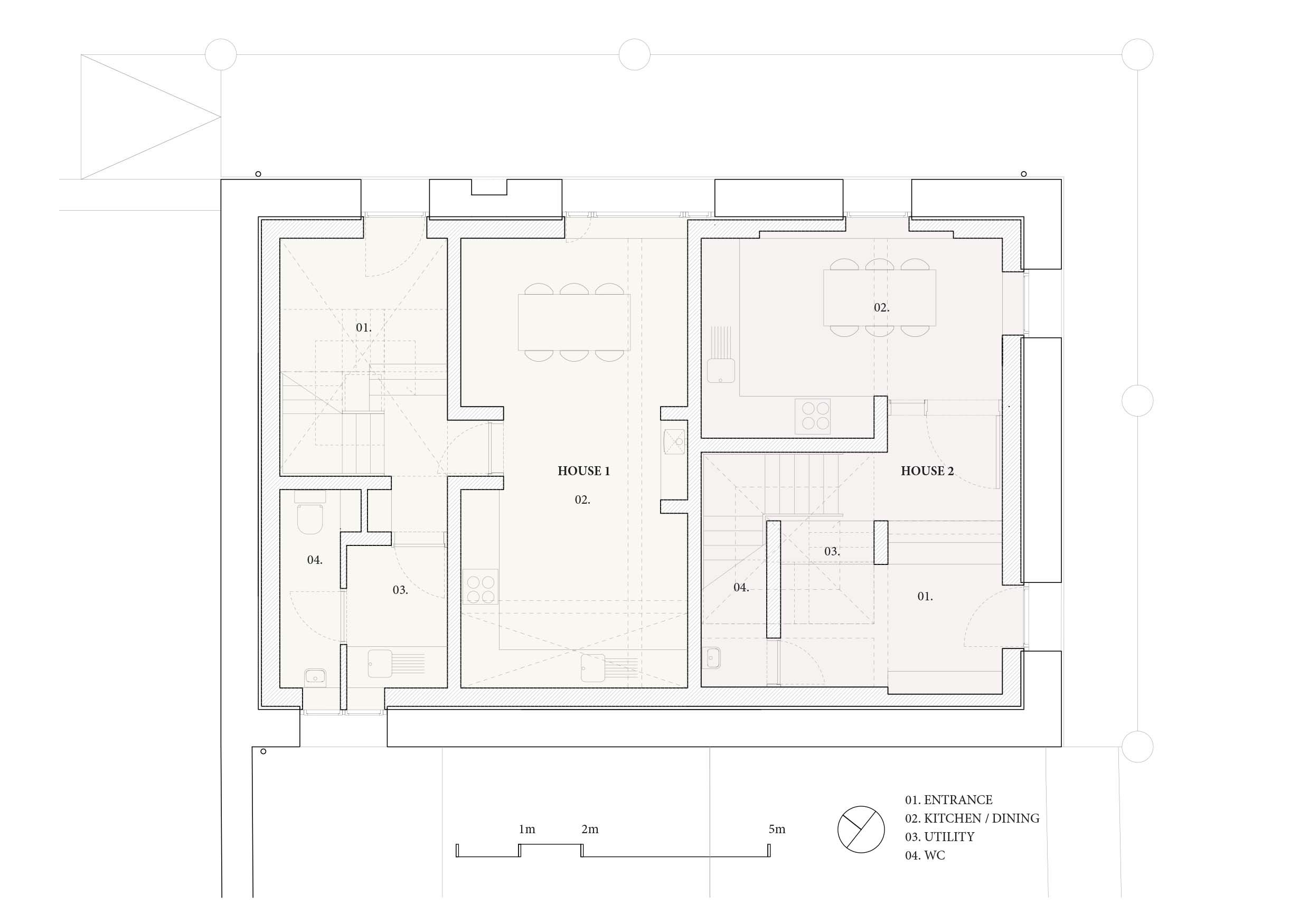

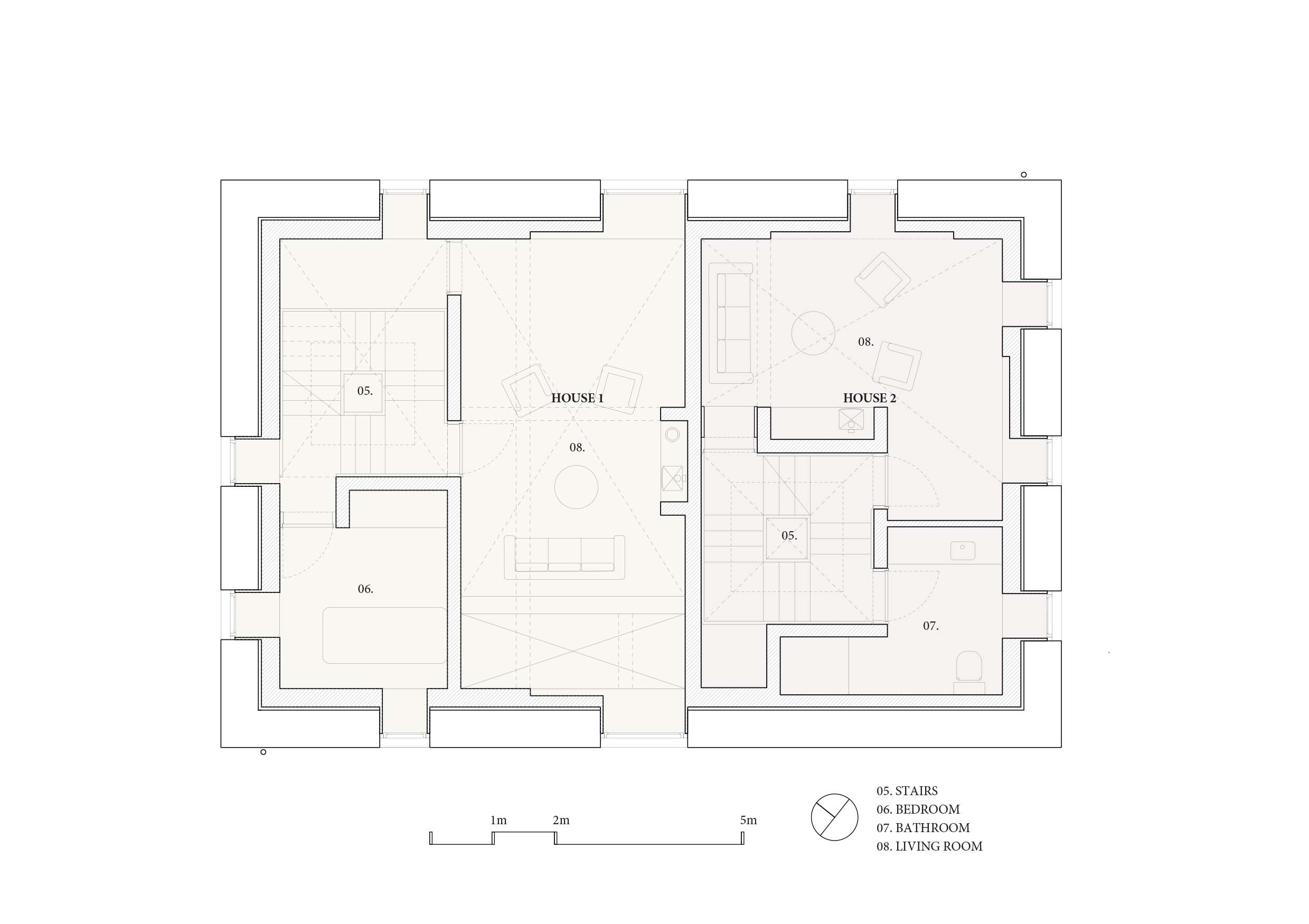

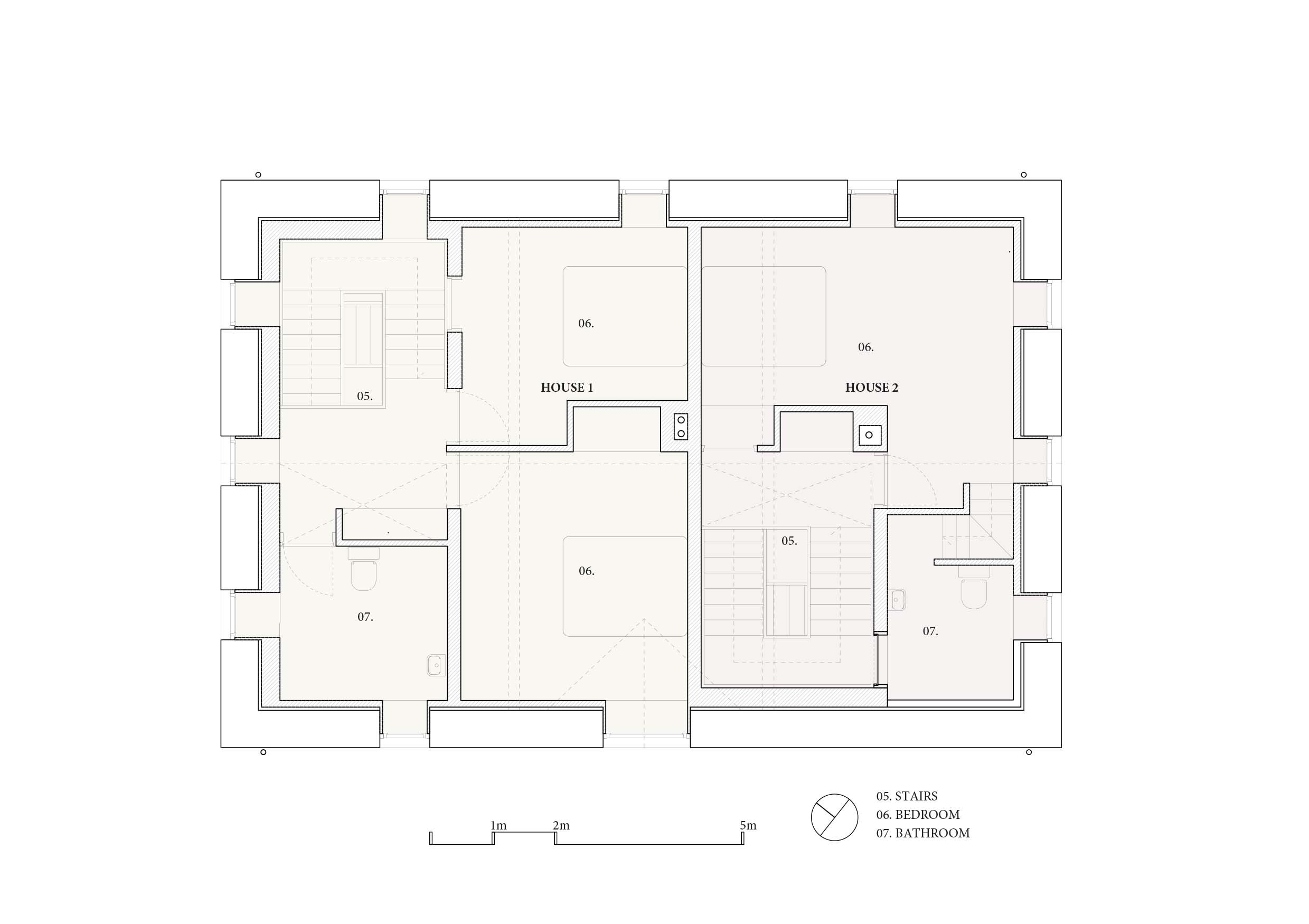

These constraints suggested a project of two tower houses, one larger than the other, dividing the building not in the middle but along the north side of the central opening so as to conserve the external elevation. Both towers are then organised as a split level arrangement of rooms around steel stairs that wind up through each, drawing light all the way down to the ground floor entrances. The ground floor is in turn raised 600mm above grade on a concrete plinth, with the lower entrance area containing no services that might be damaged by water in the eventuality of flooding.

The design began with a photographic and measured survey of the building. While the existing warehouse floor boards were rotten, the original North American pine rafters, joists and lateral beams were in very good condition. These were retained but re-configured as a permanent shuttering to cast new structural polished concrete floors that had to align with existing window locations, the new stairs levels and to provide adequate floor to ceiling heights. The removal of floors entailed that the external walls would need to be tied back to a new structural inner leaf. The vertical arrangement meant that the stairways should be one hour fire protected. Central heating would be provided by air source heat pumps located on the rear roof.

When working with existing building fabric, dialogue is vital. This and a degree of tolerance in the design drawings that allow nimble reactions to the inevitability of compromise. This was the main lesson of the project, much of what I had presumed to know about design had to be re-tooled toward reacting to contingency.

All that said, there were more drawings made during the construction period of this project than in the design period, usually to resolve as-found and as-built conditions. But these drawings are somewhat different in their nature to conventional design drawings. These drawings were part survey of what was now partially built, part speculative, usually of specific situations that required ‘re-abstraction’ to see how we might resolve them. The gift of working in this way is that it is easier going, less anxious, and produces unforeseen conditions, unforeseen aesthetic qualities. It eludes conformity.

Lucius Burckhardt describes working with existing buildings succinctly, as long ago as 1979 in The Minimal Intervention:

Until now , only new buildings and so called authentically restored buildings old buildings were considered beautiful. Under the influence of various art movements and art theories, we are growing more receptive to the beauty of the altered building. This is true not only in regard to the natural effects of time, which is to say weathering and patina. Emancipatory aesthetic information is yielded also by positively addressing structural conditions under new circumstances, that is by converting a building.

Constructed in the vacuum of the pandemic, the project became a strange internalised world, continuously shifting. Ideas got forgotten and replaced by new ideas as the building changed, as people changed. The extended duration of the project also allowed space to see and adapt new references such as the stairs in South London Gallery by 6a Architects, which informed the making and colour of the two stairs in this project.

Contained by its protected envelope, the emerging project was shaped by constraints, but also my own intent. Its architectural ambition is present in the careful positioning of things, the judgement of adjacencies. I like the word ‘polysemy’ to describe this idea, whereby a things affect is ambiguous by virtue of its adjacency to another thing. In this project we see many things held just apart.

For me, the ‘emancipatory aesthetics’ described by Burckhardt are the tangible possibilities inherent in breaking with the orthodoxies of design. They are the strange details that occur when one is steered by the inevitable compromise struck between existing fabric and additional layering of more fabric. Planning and strategising in the conventional sense are broken, and reacting, repairing, fixing, ‘making do’ become more appropriate themes.

These emancipatory aesthetics put simply are the dissonant products of such dialogue, that do not conform to what is commonly appreciated within our architectural community as ‘good’ by which I mean neat, tidy and ‘tasteful’ ;)

NOTES

Published March 24th 2023.

Many thanks to TOB Architect for sharing this project with us.

Completion photographs © TOB Architect.